“Trauma-Informed Design: Transforming Correctional Design for Justice”

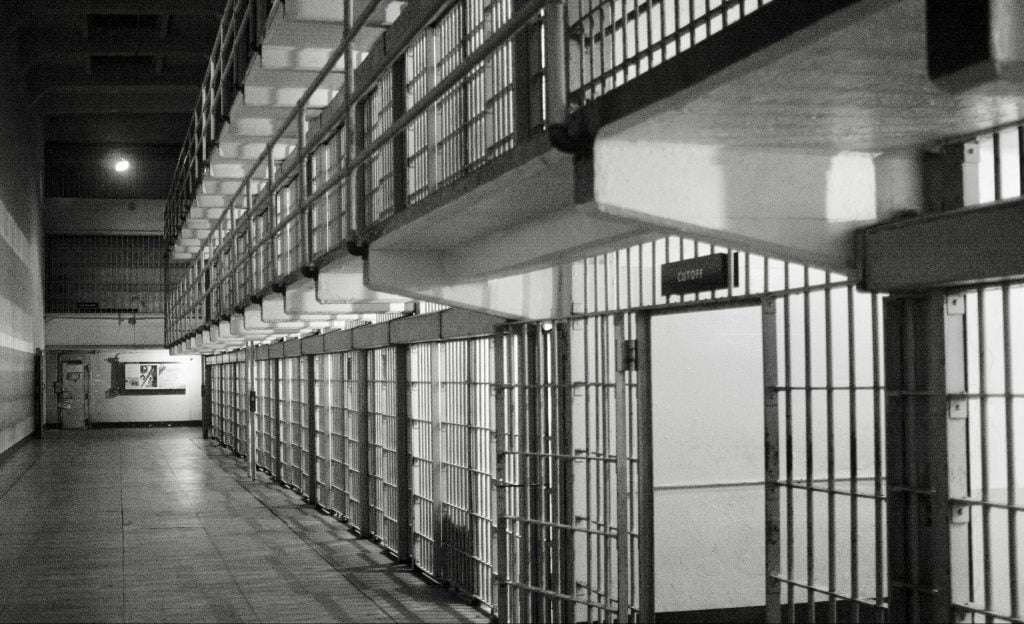

What is the role of Trauma-Informed Design in reforming correctional facilities? With 7.3-million Americans in some level of corrections (prisons, jails, probation or parole), it is clear we are setting up those who are incarcerated to fail. The glaring truth can be seen in recidivism rates of 76.6 percent after 5 years! IDP explores the injustice of racial inequity within correctional design.

IDP’s own Janet Roche leads an expert panel of Christine Cowart (Cowart Trauma Informed Partnership); Jana Belack (PlaceTailor); and Dana McKinney (Gehry Partners) to examine the history and future of corrections design, and and how Trauma-informed Design can be used to reform it.

In this webinar, Inclusive Designers Podcast and the Boston Architectural College (BAC) joined forces to discuss the role of designers in providing safe and sustainable facilities for corrections, with a focus on offering design solutions to social inequities in this environment.

Moderators:

Janet Roche- BAC Alumni Council, BAC Adjunct Instructor & Design for Human Health Graduate; Owner of Janet Roche Designs, LLC, & Host of Inclusive Designers Podcast. Contact: janet@inclusivedesigners.com; www.inclusivedesigners.com; plansbyjanet.com

Christine Cowart– Senior Policy Analyst; Trauma-Informed Consultant, Owner of Cowart Trauma-Informed Partnership. Contact: christine@cotipusa.com; www.cotipusa.com

Panelists:

Jana Belack, Leed AP BD+C– BAC Adjunct Instructor, Lead Designer PlaceTailor. Contact: janabelack@gmail.com

Dana Mckinney, AIA- Architect and Urban Planner, Gehry Patners, LLP, Co-founder: Black in Design Conference; Map the Gap; African American Desin Nexus. Contact: dana.e.mckinney@gmail.com, www.danamckinney.com

Agenda:

“Intro: Trauma Informed Design/Transforming Correctional Design” – Janet Roche

“Implications of Understanding Trauma on Correctional Design”– Christine Cowart

“Evolution of Correctional Design: Pros & Cons for Future Designs” – Jana Belack

“The Future of Corrections with Urban Design in Mind” – Dana McKinney

“Questions & Answers on Implementing Design for Justice Reform”– Entire Panel

“Janet: Hi, and welcome to ‘Transforming Correctional Design for Justice Reform’. I’m going to be one of your hosts, Janet Roche. I am part of the class of 2016, and I’ll get into my bio at some point. I’m coming to you right now from the lovely state of Vermont.

I’m honored to be here for the first or what the BAC hopes to be regular inspired talks over the years. And the founding week of the BAC we’re going to showcase all different alumni and students and teachers and special guests about the inspiring work that they’re doing. And that also includes yours truly right now. And we have Jana Belack, who is also an alumni for this particular panel. So I also want to thank the leadership of President Mahesh Dass for, in the office, for coming up with this grand celebration this week.

And we’ll talk a little bit about science and what that means in terms of corrections and corrections design, and justice reform. But we’re going to add a little piece, which is going to be about trauma and what does trauma mean and how does that also affect humans within the built environment and in this particular case in corrections.

So, just want to do a couple little laundry, you know, pieces here. First of all, I have a big old card that says we might be having technical difficulties. So we all recognize that, I think by now, this is the eighth month of going into the pandemic, and we are all very aware that sometimes things don’t go as planned, but we will try to get it remedied as quickly as we can.

But just so you know, it will be taped and it will be put on the BAC website at some point, and then also I will go in, and I’m also the host of Inclusive Designers Podcast, and it will be on our website as well, along with a whole bunch of lists of links. I always say, it’s going to be out by Monday. I’ve done this before and that’s never the case. So look for it maybe in a week or so. So I’m just going to put that on out there as a disclaimer.

Also, I also want to make sure that when we talk about prisons or whether we talk about corrections, we’re talking mostly about prisons and, but there’s a difference between prisons and jails. So I just want to kind of go over really just quickly in a nutshell, jails are really about short term. They’re usually run by local law enforcement and government agencies, and they’re designed to hold people, awaiting trial or are serving some sort of short sentence. Whereas prisons, you got to think of it more in terms of long-term usually operated by state government or federal bureau of prisons, otherwise BOP in case that comes up. It’s usually serious crimes, felony felonies. They also have a, the difference between minimum, medium and maximum and security, types of facilities in these buildings.

And it was interesting, just a little side piece and we can roll back into this at some point, I was just trying to see if I could get a little more of a well-defined, well, just real good, better definition of prisons and jails. And, what I found though was as, I found some sort of quote, that was defining them and they literally said they go, “prisons, were designed to be an unpleasant experience”. So we will circle back with that particular thought as well. And I think that that really kind of sums it up.

We’re also going to be really kind of talking about adult prisons. We’re not talking about juvenile. Although a lot of the statistics are kind of, there’s not a lot of studies, and there’s a lot more nuances with juveniles versus, adult correction facilities. So keep that in mind. That’s also on the card.

So I wanted to tell you a little bit about myself. And a little bit about my journey, both getting to the BAC and to some degree, and, and also how this particular program came to be. So I own my own company, Janet Roche Designs, and I am also the host of Inclusive Designers Podcast with my co-producer Carolyn Robbins who’s on this call. And I’m also the co-founder of Trauma Informed Design Initiative, with the BAC’s very own newly minted director of Design for Human Health program at the BAC, probably one of the smarter moves the BAC has moved with, Dr. J Davis Hart. So that’s a little bit about myself. I got my Master of Design Study in Design for Human Health in around 2016, although as Eliza will attest, there was a little controversy this afternoon about when I actually graduated, I do have an actual diploma. I can show that to you. But I also teach Biophilia. I’ve taught a few other classes, but primarily I’ve been teaching Biophilia, which in case you don’t know is the innate attraction to nature. And I think it’s an important piece to mention just because it is in its assets, it’s about restorative environments, and how we can also put into the built environment. So we might thread that in at some point for the conversation.

So back in June, Eliza Wilson had this fabulous idea. Let’s do a whole day of talks. And so I asked, Dr. J Davis Hart to come be my co-host for that talk. And we discussed, we did a piece on reopening schools after COVID and sort of the effects of what trauma will kind of present itself and how we can, as designers can help minimize that and have more successful outcomes. So it was a, a well-received talk. And so, Eliza, myself, and I can’t remember who else was in the room, I do know the other, one other person that was in the room, that was Rand Lemley who is the co-chair of the BAC’s alumni council and also an instructor who actually works with Jana Belack on Corrections. And so he said, Hey, why don’t we do a piece on correction and without thinking about it, I really had a moment where, it was very unlike me, I jumped at the chance. And it was so, it was really so unlike me, I, I couldn’t get over how aggressive I was about wanting to do this particular piece. I, I dare say it was like, ‘Ooh, ooh, ooh, me, it’s mine. It’s mine. It’s mine. It’s mine. I want this, I want this piece’. So Rand, forgive me if I ran you over, but I really wanted to do this. Then I started driving in my car a couple of days later, and I thought to myself, why did I do that?

Why did I get so like, so passionate about wanting to do this piece? And lo and behold, I had actually forgotten in my previous life, and this is not some sort of weird karma thing. It was a long time ago. I was a social worker and I worked, in an incarcerated facility in Boston for juvenile delinquents. It was a full blown, locked down environment for juvenile delinquents. And I lasted about, well, 1 year of my internship and 2 years thereafter. And I, I just got so frustrated. And I felt like we weren’t really, even though Boston was, it was so incredible about being really forward thinking at the time, again, this was a while ago. But it was just, it was too hard. It was just too hard because it really wasn’t restorative. We were, I felt like we were just holding them until we moved them into, the adult prison system. And I really was upset by that. And then fast forward, I was in the DHH program and I remember very specifically as to where I was, and we were talking about the importance of light and air and the whole program of Designing for Human Health is about just that. It’s about human health. And I remember kept thinking, what about the prisons? What about the prisons? Because when I was in, when I was working with the juvenile delinquents, we used to do part of that program. Some of you might remember it, it was called ‘Scared Straight’.

And so we would take the juvenile delinquents and we would bring them into the adult prison system. And I don’t remember the prisoners yelling at them, which was sort of what was the norm, but they kind of talked to them and told them how, you know, like, don’t end up here. Little side note, even though that particular type of work got a lot of accolades in the late, it started in the late 70s and worked its way through the 80s. Go figure it, it didn’t work. And again, that’s a lot about trauma and again, it was forward-thinking for its time, but it just, it’s not something that kind of works.

So at some point, when I started to think about what I was doing at the DHH program and realizing somewhere in the back of my mind, I’m like, I really want to do something, I really want to do something along those lines, I’m passionate about that. But first I also wanted to do a lot of work with the Adaptive Sports program. And this is sort of my lead in as to how I go and introduce, Christine Cowart who I met in the Vermont Adaptive Skiing Sports program. So without further ado, I have Christine, if you can go and pop on, that would be great.

Christine: I’m very excited to be part of this talk today. Thanks for having me, Janet.

Janet: Thank you so much, Christine. So Christine, Christine is going to be my co-host today and I couldn’t think of a better person to do this with. Without, before I get into her biography, let her do her, her thing. I met her through the Vermont Adaptive ski program and, they were doing a piece on trauma informed, just trauma informed, right? It was trauma informed therapy. And I said to myself, I already know this. So, really unlike me. I know I keep saying that, but I just sat in the back. And I thought to myself, it was a great way for me to be like, show myself and then get out while, while, you know, she had a nice little, I’m sure she had a nice presentation to get out. Not only did I find myself inching on up the, the seats because she broke it down in such great, in a great way, in a fabulous way. She knows the story better, I probably tell it all the time. I might’ve followed her out into the parking lot. And I was like, we’re going to do a lot of bunch of things together, and I think she thought I was out of my mind. But here we are with the second piece that we’re doing it for the BAC and I couldn’t be more thrilled that you’re my co-host for this particular piece. So let me introduce you again. She’s my co-host. She’s a trauma informed consultant and founder for Cowart Trauma Informed Partnership, and is the senior policy analyst here in Vermont. So welcome Christine.

Christine: Thank you.

Janet: It’s been quite the journey. We started this journey in June and it was pushed back. And it was pushed back and now we’re here, which actually this is fabulous. And again, we couldn’t thank the BAC more for being so proactive and also taking a bit of a chance on our programming and Christine, you and I we’ve talked to all different types. Our first few rounds, we went through, we talked to different designers and you and I knew where we wanted to go. And a lot of the traditional designers that were designing prisons and stuff thought it was a little radical. I don’t know how else to put that. And we had some designers back out and literally had moral dilemmas about knowing what we were doing was right, but not wanting to have, not wanting to bite the hand that feeds them, correct?

Christine: Oh, absolutely. We ran into a lot of people saying, ‘I agree with what you’re going to say. And I can’t say that because it would jeopardize my career or whatever’, and I’m glad that we have the platform today to make this case. Most of my career has focused on the criminal justice system and services to families and children. Over the last decade, there’s a new understanding of trauma and how it impacts a person biologically. These are very real physical changes that happen that affect a person and as a result, affect their behavior and the behavior is what we see. And so, this has been woven in, in all sorts of other applications. You see it in healthcare, you see it in education and social services. We really need to change our approach to how we’re thinking about corrections.

And yeah, it’s new and it’s scary for a lot of people, but I’m so glad for the panel that we’ve assembled. Because we’ve got some really great examples that we can roll out today and talk to you about, we’ve got a phenomenal panel. So, I’m excited to jump in.

Janet: So, excited. And maybe what we should do is then just go into your piece. I will sign off.

Christine: Yeah. So Eliza, if you could put up that first slide before we start. I just want to let everybody know that we’re going to be talking about some topics that might be unsettling. And if at any point you start to feel upset or any kind of distress from what we’re talking about, please feel free to step away, take care of yourself. This information, as Janet said, will be recorded. You can come back at any time. And I just wanted to also say that there’s other techniques you can use in the meantime, if you want to try to sit through it. They’re grounding techniques you can use to try to touch and feel your physical surroundings, focus on your breathing. Notice what’s happening around you in the real non-virtual world. And that can sometimes help you lower your stress response rate. By all means. If you need to reach out to someone, please do so. you can reach out to someone you trust in your life or use that number on the screen.

And without anything more, I’d like to jump right in, into my piece, which will explain what trauma is and how that relates to correctional design.

Presentation (Video): “Hello, my name is Christine Cowart, and I’m going to talk about what trauma is, how it’s related to correctional facilities and how we can use that knowledge to transform correctional design for justice reform.

I am a certified trauma professional and human services policy analyst with a focus on criminal justice and services to children and families. Through my career, I have worked in correctional systems and facilities in three Northeastern states. Most recently, I served with the Vermont Department of Corrections, before moving to the Department for Children and Families, which is responsible for administering the youth justice system in this state.

I’d like to start out by talking about what trauma is and how it can impact a person. In 1998, a medical practice in California noticed that some of their patients were doing significantly better than others with seemingly similar backgrounds. They identified ten common characteristics that when experienced as a child could result in poor health outcomes. We refer to these as ’Adverse Childhood Experiences’ or ACEs for short. ACES can have lasting negative impacts throughout a person’s life, including increased injury, effects on mental and maternal health, increased infections and chronic disease, and the adoption of risky health behaviors and loss of opportunities.

I want to stress that this is risk, not certainty. There’s a lot of things that can impact how a person is affected by adversity including exercise, life choices, personal relationship and therapy. But as you can see from this list, the effects of these experiences is not just psychological. Having experienced adversity can quite clearly affect a person’s physical health dramatically.

This data shows the prevalence of ACES across our nation. But it’s based on information collected through telephone surveys and it’s believed to be significantly under-reported. Evidence indicates that at least 78-percent of the US population has experienced at least one traumatic event in their lifetimes. In addition to under-reporting, the difference between statistics is explained by recognizing that the data on this chart only includes events that happen prior to the respondent turning 18, and understanding that ACES only represent one group of potentially traumatic events. There are disparities in the rates of adverse childhood experiences within the population.

Studies routinely show that people living the disability are more likely to have experienced ACEs than the general population. This is important to keep in mind because we know that people with disabilities are also more likely to have involvement with the criminal justice system. The results of the national survey of children’s health show that there are racial disparities as well.

This annual nationwide survey asks parents of children under the age of 18 about ACES experienced by their children. The results show that black children are more likely to have higher ACE scores compared to white children, and black children are overrepresented among children with two or more ACEs.

There’s also evidence that the more ACEs the person experiences, the more they’re at risk for negative outcomes. This is called a dose response, and it’s seen across virtually all areas, including the adoption of risky behaviors, such as alcohol and drug misuse. It’s believed that individual increased their usage of these substances as a means of self-medicating in response to the traumas that they’ve experienced.

So if there are other traumatic events beyond ACEs, what is trauma? The substance abuse and mental health services administration defines trauma having three parts. The experience that happens to the individual. The individual has to believe that it’s physically or emotionally harmful or life-threatening, and it has to have lasting negative effects throughout the individual’s lifetime. The recognition that trauma can be caused by more than just personal events, which are represented in this photo by the tree, resulted in the concept of adverse community environments. We see those situations in the roots of this image.

Traumas can be produced by structural environments, which prevents people in communities for meeting their basic needs. Examples are racism, poverty, or housing. Trauma also extends beyond the individuals who are directly related to, or witnessed or experienced violence. An example of this is someone who lives in a community where a school shooting happened but wasn’t directly affected. If a large portion of the people in their community were, the way the whole community interacts can change, and that can affect the people who weren’t directly involved and might not have known someone who was.

Together, at risk community experiences and adverse community environments are sometimes referred to as the pair of ACEs. We now recognize that natural disasters and climate crisis can also be traumatic, as illustrated on the right-hand side of this image. There are three realms of ACEs that can create traumatic events but intertwined throughout people’s lives and affect the viability of families, communities, organizations, and systems.

Traumas can take on different forms. There are acute traumas, which are usually one-time events like an accident, death of a loved one, weather event or assault. Trauma can also be chronic or occurring over time, such as ongoing abuse or neglect, combat situations, or even multiple unrelated traumas.

Trauma can be incredibly complex, such as repeated uprooting, homelessness, human trafficking, and living as a refugee, or experiencing more than one type of ongoing abuse or neglect. And then there are system induced traumas, such as the removal of the child from a family and placement in foster care, sibling separation, having to testify in court against family, and living in extreme poverty.

We all experienced stress in our lives. If I do the same thing over and over and never change things up, I’m feeling pretty comfortable, but I’m also not learning anything. I’m in my comfort zone. In order to learn something new, I have to step outside that comfort zone, even just a little. When I can do this with a feeling of relative safety, that’s positive stress, and that’s when learning happens.

When those boundaries get pushed even more. And I start spreading further out and feeling as though maybe this wasn’t such a good idea. I get nervous. My heart starts racing. I might get blinders or tunnel vision. I feel as though things might get really messed up, and I’m not happy about being in this position. But if it’s relatively short-lived or I have a person or two to process it with after, I might realize I’m relatively okay. And came through it unscathed. I might even feel as though it wasn’t so bad after all, and I could try it again. That might even make me excited because next time I might not be so nervous because I know I had a good outcome this time. This is called tolerable stress.

It’s when those boundaries get pushed even further to a place where I seriously feel as though I can’t handle it. There’s no end in sight. Or I feel as though my life might be in danger. I have no one to process this with afterwards. That’s toxic stress. Toxic stress is the mechanism by which adversity becomes traumatic. Two people can experience the same thing and it might be traumatic to one and not the other. Genetics has something to do with this because some people have a genetic makeup that protects them from the anxiety and depression, but very frequently the difference is whether the person has a supportive adult to rely on who can buffer the person in what would otherwise be traumatic.

When your brain detects a threat, the amygdala or survival brain releases adrenaline, norephrine, glucose, and cortisol, and it revs up your body and your brain and activates your ‘fight, flight or freeze’ response. At the same time the prefrontal cortex thinking part of your brain assesses the threat and either turns up or down that response. Following trauma, studies show that the amygdala is hyper-reactive and the prefrontal cortex is less activated, so that can result in the person experiencing hyper arousal, hyper vigilance, and increased wakefulness and sleep disruption.

In addition to changes within the brain, experiencing toxic stress can result in other physical changes to a person’s body. This image shows some of these physical impacts, and I’d like to highlight that there’s emerging evidence that suggests that changes to genetic markers may be passed down from generation to generation. That could be one of the causes of what we see as intergenerational trauma.

Let’s talk about trauma as a pathway to crime. What do I mean by that? There’s an undeniable link between childhood trauma, and leader criminality. This has become especially true for people who are convicted of drug and property offenses. We know that people who have experienced trauma are more likely to engage in risky behaviors, including the overuse of alcohol, or the use of other substances. Perhaps as a means of self-soothing or self-medicating. Since we’ve outlawed the use of many of these substances, rather than treat it as a medical concern, it is often a direct pathway to criminality. We also know that many people convicted of property crimes engage in that behavior to increase their ability to acquire illicit substances when other sources are no longer available.

Now that we’ve introduced community complex and system induced traumas, we can look at another finding from the ‘National Survey of Children’s Health’. The survey includes the question: “To the best of your knowledge, has your child ever been treated or judged unfairly because of his or her race or ethnic group?” The results show, the black children who’ve experienced individual discrimination have higher rates of ACEs. This is important to note when we talk about the prison population, because a disproportionate percentage of incarcerated people identify as black.

Here you see the 2018 racial disparities in prison incarceration rates adjusted for population. Why is that? Structural racism. We already talked about how people of color are more likely to experience adverse childhood experiences and that community factors such as poverty, involvement in the child welfare system, and experiencing race can be experienced as trauma.

There’s also a phenomenon called the school to prison pipeline that plays a role in it. Studies show that when children are disciplined at school or in the community, children with disabilities, or who are of color, receive harsher penalties for the same behavior as their white peers. While a white child might have his parents called for tripping another child during recess, the child of color might have to sit out or receive an in-school detention. Over time, students build up a record or reputation of having a behavior problem and their punishments continue to escalate to include suspensions and even expulsions.

As the children age, these attitudes carry over to the juvenile justice system. Children of color are more likely to be arrested by school resource officers and more likely to receive harsher sentences. Statistics show that black people are disproportionately stopped by police on the street, and more likely to be arrested. Black youth are arrested far out of proportion to their share of all youth in the United States. Black people are disproportionately serving life, life without parole, or virtual life sentences. In additional to this, Black and Hispanic people are also more likely to be detained in jails before their trials, because they can’t pay the bail.

And people who are incarcerated report, high rates of childhood trauma. I want to take a moment here to talk about children who grew up with ongoing abuse or neglect on homes with domestic violence. We know that when there’s violence within the home, there’s at least one family member who’s experienced trauma. In families with children, the dynamic is even more complex. Parents living with unresolved trauma are often not available to fully support their children.

Children who grow up with chronic abuse or neglect, don’t learn how to form solid attachments or understand cause and effect. This is because babies and children learn that when they cry, or show a need, a parent satisfies that need. In a home without consistency, children never learned from this basic feedback route.

If a person doesn’t understand the cause-and-effect relationship, they may not understand or be able to predict the consequences of certain actions. This can lead to them behaving and reacting to circumstances, without a clear understanding of why some responses are acceptable, and others are not. This can lead to behaviors that others would describe as poor choices, right up to, and including criminal behaviors.

In addition, parents are supposed to be purveyors of safety. So if they’re not safe, how can a child feel safe in the world? To complicate matters, as they grow children model their relationships off of what they see at home, which can lead to cyclical, intergenerational trauma, and choices that result in criminalized behavior. Another remarkable study of incarcerated men by the Missouri Department of Corrections recorded near universal trauma in adolescence.

In addition to childhood trauma, incarcerated people report high rates of trauma throughout life, as compared to community rates. The sexual trauma rates here are worth noting as frequently homeless youth have high rates of being victimized on the streets.

Incarcerated females appear to have different risk factors for offending than male offenders. Incarcerated females show elevated rates of interpersonal trauma, substance dependence, and associated symptoms of post-traumatic stress thought. One study showed the majority of women in jail experienced multiple types of adversity and interpersonal violence in their lives.

Incarcerated females report greater incidents of mental health problems and serious mental illness than incarcerated males. Women with SMI were more likely to have experienced trauma, to be repeat offenders, and to have earlier onset of substance abuse, and running away. The study found that victimization appears to increase the risk of experiencing mental health problems, which in turn is related to increased likelihood of criminal offending.

We’ve talked about how experiencing trauma can affect a person’s understanding of cause and effect leading to criminal behavior. And about the link between self-medicating and criminality. Another reason for the high rates of trauma among incarcerated individuals maybe because some of the symptoms of trauma can lead to behaviors that we might misinterpret as a person refusing to cooperate. These behaviors can be seen by school officials, police, and other authority figures as non-compliance, which can result in stricter penalties for minor offenses.

Over time, a person can accumulate a record that might lead to longer, harsher sentences. Similarly, there are symptoms of trauma that appear from a hyper-vigilance or constant state of arousal that can be misinterpreted. These can be viewed as though the person that was being intentionally hostile, especially when they’re feeling threatened, and can have a similar impact on a person’s outcomes. There are even symptoms which might be overlooked. The results from a person disengaging, feeling numb or tuning out. So if the person shows no outward signs of distress, authority figures might not suspect the history of trauma.

Now that we understand trauma as a pathway to prison, and its prevalence among inmates, we need to talk about the prison environment itself. There are things that can make a person who has experienced trauma feel as though it’s happening again in the present reality. These are referred to as triggers.

Triggers activate the ‘fight, flight or freeze’ response, and limit access to the higher functions of thought because the person truly believes that their life or wellbeing is in danger. Common triggers include unpredictability, sensory overload, feeling vulnerable or frustrated, confrontation, or experiencing something that reminds the individual of a past traumatic event. Most, if not all of these, are commonplace in traditional correctional facilities.

Common triggers in correctional facilities include constant lighting, and never being able to get a good night’s sleep. Imagine how that would affect your healing and wellbeing, and your ability to regulate your emotions, to interact in a calm manner. Loud noises or doors slamming. I worked in one facility where the doors were so loud, I never got used to it. Even knowing this about the place, when the doors were closed, I jumped almost every single time. Imagine what it would be like to be someone with significant trauma who is required to live there and knows that they can’t move.

A lack of privacy, especially in bathrooms. A fear of victimization. The lack of good touch. All sexual relationships are prohibited even if they’re consensual. In many facilities, there are even rules about touching visitors. In some you can’t touch at all. In others, people who are incarcerated are strictly limited to a hug or short touch upon meeting or leaving. And intrusive body searches. These are especially brutal for individuals who’ve experienced prior sexual victimization.

A growing body of research indicates that solitary confinement in which an inmate is held in isolation and which is used as behavior management technique in prisons is ineffective. It can have negative impacts on mental health. As we’re looking at these effects, it’s important to know that this is no exception to the disproportionality and punishment. Black men and women are overly represented in solitary confinement throughout the nation when compared to the total prison population,

Here you can see some of the harmful psychological effects of long-term solitary confinement. It’s important to note that these effects are magnified for juveniles whose brains are still developing, and people with mental health issues who are estimated to make up one third of all prisoners in isolation.

The rates of violence in the US prisons leads to the further traumatization of inmates. Incarcerated persons may also be pressured to make crimes while in prison. This frequently is related to smuggling or selling drugs or cell phones. They might also feel the need to join or befriend a gang for protection, but this can lead to pressure, to make illegal activities. It’s understandable how these experiences could exasperate the symptoms of trauma or even be traumatic themselves.

All this brings us to considering correctional design with a new mindset. We have to rethink with the trauma informed approach. Recidivism is the likelihood of re-offending. According to the National Institute of Justice, almost 44-percent of the recently released return before the end of their first year out. About 68-percent of individuals released in 30 states in 2005 were arrested for new crime within three years of their release. And 77-percent were arrested within five years. And by year nine, that number reached 83-percent.

In 2004, 17-percent of the people incarcerated in state prisons and 18-percent of people in federal prisons said they committed their current events to obtain money for drugs. Statistics show, these are typically property and drug offenses, not related to violence. We know that drug use is linked to trauma, which prisons worsen. And we know that incarceration is not an effective deterrent against future crime. So it seems we need a new approach for non-violent and drug offenses.

Restorative justice emphasizes repairing the harm caused by criminal behavior. It’s best accomplished through a cooperative process that includes all stakeholders. This can lead to a transformation of people, relationships, and communities. When compared to traditional criminal justice responses, restorative justice programs show promising results of being more effective at achieving victim offender satisfaction, offender compliance with restitution, and decreased recidivism of offenders.

We talked about the possible impacts of trauma. We also mentioned that just because a person experienced trauma does not mean they will experience the negative outcomes or risks associated with that trauma. Resilience is a person’s ability to overcome serious hardship. And building a person’s resilience is the number one way to protect against the risk associated with trauma.

A person’s resilience can be built up over time through consistent supportive relationships and spending time in the positive and sometimes tolerable stress zone. As opposed to prisons, which amplify existing and add new traumas to people incarcerated, the practice of restorative justice, work to build their resilience, which can interrupt and impact the past traumas by lowering the individual’s stress response and giving their system the chance to rest. And it’s in this space that healing can happen.

So in implementing a new mindset for justice, if you must work on prisons, I implore you to mitigate or eliminate as many of the triggering aspects of correctional facilities as possible. However, I urge you to think about correctional design as designing new restorative spaces, not prisons. For it’s here that you can make the greatest impact.

Framing correctional design as designing for restorative spaces gives you the opportunity to move past minimizing potential triggers. You can be on the forefront of a new movement for social justice and equity through the spaces that you design. In creating spaces in which healing can happen, you can be part of reducing recidivism, building resilience, and providing a previously elusive sense of physical and emotional safety. And that is the very epitome of trauma informed design.”

Janet: Christine, that was wonderful. As always, you’re able to break it down in these beautiful, easy to understand bite sized pieces that are just, it just makes it so accessible and understandable. And so for that, I thank you. I’m always struck, and always a little heartbroken every time I read the recidivism rate. You know, the 44-percent in 1 year, 76-percent, I think 76.6-percent in 5 years, and 89-percent in 9 years. And so clearly what we’re doing is, at the moment what we’re doing is wrong. We, we go into some of the history of it next. I’ll let you introduce Jana, but it is, it’s really hard to swallow and clearly what we’re doing is wrong. Do you have any parting words, in terms of design? Those, those triggers, I know you always talked about the doors. Maybe you want to start with that.

Christine: Well, it really comes down to the evidence of trauma and how it can affect the person is so well-documented, there’s no doubt about it. Trauma informed approaches are being integrated, as I said earlier, in all sorts of other fields where we’re dealing with humans, in health education, social sciences, and services. So, given what we know about how people engage in criminalized behavior, and why they engage in that behavior as a self- soothing and a self-regulating means in many cases. And the fact that carceral environments are so trauma inducing, like you said, this is, the doors. That’s the one that I literally jumped every time a door closed in that one facility. It was just overwhelmingly loud.

Janet: And at any time, I mean, you don’t even have to have been in a prison and all you, you, all you have to do is watch a TV show, and you know that iconic, you know clang.

Christine: Oh, I’ve, the funny thing is, is I’ve been in a lot of them. And in this one, it literally was louder than anything you could imagine. And it was, it, it made me feel like it was done intentionally. And when I spoke to people who worked there and I talked about, well, is there some way that you can hold the door so it doesn’t slam? And they’re like, well, we’re moving too quick and we do too much. And we have to be places too, too suddenly, and there’s too many people moving all the time. It just doesn’t make sense. But to get from one part of the facility to another, you had to go through the central operation center. So you couldn’t really move about in your day to day life if you were living in one of these facilities without having to go through these doors constantly. And it’s just a constant reminder of where you are, and that you’re, it’s oppressive, and it just weighs on you. And so, given everything we know, as I was saying, of why people are there, what the environments do to a person, how that would affect your hyper vigilance and your inability to turn off your stress system and just reduce your stress and really be able to bring that down. And be able to control your emotions in a way that we would expect the person to, especially to show that yes, I’m okay to be released back into society. There really is no reason for us to continue building prisons as we know them to exist, when we look at them as a response to most crimes, when we think about recidivism rates and how they’re not working. I mean, we essentially are using prisons as punishment, not as a way to make a person more safe to be back out into society.

Janet: Christine, I’m going to let you go and introduce Jana now and, I’ll see you on the, on the flip side.

Christine: Sounds great. So, I would, have the great honor of introducing Jana Belack. She is a 2-time BAC graduate, and she is going to come on and talk with us about the evolution of carceral design over the last 200 years, and ideas for the future and where we would like to move. Hi, Jana, how are ya?

Jana: Hi. Good. How are you?

Christine: I’m doing great. Can you tell us a little bit about what your talk is going to cover?

Jana: Well basically, like you said, it’s an evolution of the design of prisons in the United States. Over the past 200 years, we have seen several times of reform and these reform theories were greatly, reliant on the architecture to fulfill the theories. So, what I’m looking at here is an evolution from starting in the 1820s and talking about these reform theories. And I think it’s really important to note for today because this is what our, incarcerational landscape has, is, it looks like now due to all these times of reform, cause each time there was a reform, it’s not that we discarded the previous ideas and designs, we kept adding and building. And this has led to us having over 22-hundred prisons, federal and state prisons, in the United States.

And through the presentation, you’ll see the different examples of this. And these buildings have really stood the test of time as most of us know and understand that prisons are typically built from concrete and steel and they’re not easily adapted or demolished. So we continued using these based on the size and our need to over-incarcerate.

Christine: Yeah, it’s a shame that it hasn’t changed much.

Jana: It really is.

Christine: I’m really excited to see what you have to show us. So why don’t you jump right in.

Jana: Great. Sounds good.

Presentation (Video): “Hello everyone, my name is Jana Belack, and I’m here talking about Transforming Correctional Design for Justice Reform. A little bit about me… I am a lead designer at PlaceTailor here in Roxbury, Massachusetts, and a 2x graduate of the Boston Architectural College. In 2010, I graduated with my Bachelor of Design Studies in Sustainable Design. And then I went on to complete my Master of Architecture in 2016 after completing my thesis, ‘A Women’s Prison; Communities for Incarceration’, which was focused on creating uplifting and supportive community settings for women and their children to end the cycle of incarceration.

In 2017, I was honored to be named the John Worthington Ames Scholar, which allowed me the opportunity to travel to the Scandinavian countries of Finland, Sweden, Norway, and also Ontario, Canada, to experience their positive approach to incarceration. Bringing this knowledge back to the BAC, myself and my co-teacher Rand Lemly created the design workshop ‘Design Convicted’, which teaches students through mixed media, the past present and hopeful future of life without prisons, and instead restorative justice practices.

The most beautiful experiences we have had teaching this topic are when you see a student’s perspective on incarceration change. Once they gain an understanding of the negative impact this has on individuals and society as a whole. At least 2 of our students went on to further explore incarceration through their master’s thesis projects. And this was an incredibly rewarding experience.

What I’m here to present today is a brief overview of the evolution of reform theories and the designs which carried out those ideas over the past 200 years in the United States. Because in order to move on to a successful future, we need to understand the failures of the past. And to also understand what we are working with because many of these buildings are still in use today.

Prior to the 1820s, jails in the United States were single room spaces where men, women, and children were all housed together without guards resulting in complete disorder. Food and clothing was also not provided. To alleviate these miseries, society, looked to the penitentiary ideas of routine and structure for reform. As the penitentiary model proved unsuccessful by the 1860s, new ideas reform based on sociology and psychology were experimented through the reformatory. The panopticon, which was a design by English philosopher Jeremy Bentham in 1791 was first constructed in the United States in 1922.

And in the 1970s, we briefly see correctional centers brought into the urban fabric to reduce travel from distant prisons to the courthouses in the city. And now here we are in 2020 when our incarcerated population is over 1.4 million. It is time for another reform. Two other times to note here are in the 1930s, we see security classifications establish the minimum, the medium, the maximum security, all, established by the crime committed.

And in the 1980s, we see the prison population skyrocket through the war on drugs. The war on drugs was meant to target the kingpins of the drug industry, but in reality, this targeted the low-level offenders of impoverished communities, disproportionately affecting black and brown people.

The 1820s saw the emergence of the penitentiary. This was based on reform ideas of the Pennsylvania Separate System and the Auburn Congregate System. Although they were rivaling designs, they had the common theory that routine and structure would alleviate criminal behaviors and they sought to do this through silence, obedience, and labor.

First looking at the Pennsylvania or the separate system, this was based on continuous solitary confinement, labor in the cells, strict silence, and they were to seek penitence from God for their criminal behaviors. The offender would remain in this space for the entirety of their sentence. As you can see in the diagram below, this is a layout of what the individual cells looked like. The doors were low, so they had to bow before walking into the space. There was a skylight above where they would look up to God and seek penitence. To the left we see a realized version of this cell in the Eastern state penitentiary. And again, you can see here, the skylight, the small door. And for the first time we’re seeing heat and plumbing in a prison facility, which is very uncommon because even in the white house at the time of the construction of the Eastern State Penitentiary, they did not have plumbing and heating.

The Pennsylvania System was realized at the Eastern State Penitentiary in 1829. As you can see in the floor plan to the left, architect John Haviland arranged the solitary cells and outdoor spaces in a radial pattern. The pink wing notes where now female offenders are being separated from the males. To the right, we see what the Eastern State Penitentiary looks like today as it is now a national historic landmark. The original plan called for single level floor plan so that each individual cell would have a skylight and an outdoor space, but due to overcrowding by the time of construction ending they added additional wings of two or three levels to house additional offenders.

Now looking at the Auburn or the Congregate System, this was based on solitary confinement at night, congregate labor during the day, and a strict rule of silence, similar to the Eastern State Penitentiary or the Pennsylvania System. Because of this new program, the individual cells were allowed to be much smaller because the offender would only be in here at night for sleep and they would leave for the day to go work in groups.

The images shown here are from Kingston Penitentiary in Canada, which is a replica of the Auburn System. To the left is a replicant in the museum showing what the original cells would look like. But by 1895, these single cells were expanded, and two individual small cells were made into one cell expanding them to 7-feet by 7.5-feet. To the right, we see a corridor in front of the cells showing how light got into the spaces. And you can see in the ceiling where it is ribbed that each rib was an individual cell.

We first see the Auburn Plan realized at the Auburn State Penitentiary in New York. Prior to the Auburn System coming to this prison, we had a one room jail, which housed men, women, and children, but in 1821, the Auburn System of the rectangular prison was built on this site. Similar to the Eastern State Penitentiary, we now see women being separated from men, but in a different way. At the Auburn State Penitentiary women were housed in cramped attic spaces with the windows blacked out so they could not spread their deviant behavior to those on the outside or the other men within the facility. Women were seen as the double deviant at this time, because not only were they committing crimes, they were not upholding their duties as a woman.

The successes of the penitentiary are few. Violence is minimized by separating individuals into their own cells, but it was not eliminated. Violence occurred when the rule of silence was broken, and physical punishments happened. Although basic life needs were met at the penitentiary, food and clothing were provided and heating and plumbing was provided at the Eastern State Penitentiary.

The failures are more common, long sentences quickly led to overcrowding. Violent punishments were common due to past theories that punishment would alleviate criminal behaviors. The design of the spaces caused severe mental, emotional, physical degradation most notably through the use of solitary confinement. And what resulted, there was no effect on crime rates. Nothing was actually done to promote reform in these facilities.

Seeing the failures of reducing criminal behaviors and the negative mental impact on those incarcerated through the use of the penitentiary, performance in the 1860s sought new theories of reform through social work and psychology. They used education, vocation and recreation as the basis for the reformatory.

Ideas of the reformatory included crime is an illness. So punishment is no longer going to reform criminal behaviors. Psychology and sociology come into play. Psychiatrists are now employed at the facilities and guards will receive training. Smaller populations address the individual’s needs. Design is meant to simulate a home life and a life outside of prison, connecting those with society. Nurseries are now common in the women’s reformatories so that the children stay with mothers and maintained familial bonds. There are no walls, fences or security devices. Now we are also seeing that those incarcerated have a voice in how it’s operated because they elected offenders within the facility to speak for them with guards and caseworkers when making decisions. And now indeterminant sentencing is also a new theory. Release is based on achievements and self-improvement, not a specified amount of time.

The reformatories for men were commonly called community prisons. And a great example of this is the Norfolk Prison Colony from 1932. This was a college campus style design where there was dormitories rather than cells and outdoor quad, auditorium and classroom learning, very similar to a college campus. The smaller populations of 50 men per dormitory allowed for individual needs being addressed. And there was no walls, fences, or security devices. The Norfolk Prison Colony still operates today, but it is now the Norfolk Correctional Center. And it’s very common to a modern prison.

A great model of the reformatories for women were the state farms. A great example, being the State Farm for Women at Niantic, in Niantic Connecticut, opening in 1918. This model was meant to teach women education, reading, and writing, cultural aspects, arts, and basically uplift them to resume their duties in society.

This was a cottage-style design, a self-sustaining farm, where the women gardened and basically grew their own food and maintained animals. There was a nursery in this facility for the women to stay with their children to maintain those familial bonds. And again, there’s no walls, fences, or security devices. They strongly urge the connection to nature, with the adjacent lake, Bride Lake, which was located beside this prison where women often swam and used for recreation. This prison is still in operation today, but it is now called the York Correctional Institution. And similar to the Norfolk Prison Colony, it has transformed into a modern prison.

Here we see the floor plans for the State Farm for Women at Niantic. The second level shows individual bedrooms for the twenty-one females who would live here. And on the ground floor, we see common spaces of the kitchen, dining room, and living room which would simulate their homelife.

The successes at the reformatory were many more than at the penitentiary. Staff and group elected counsel, representing those incarcerated, realized that cooperation is much more successful than opposition. The smaller populations encouraged and supported meaningful personal connections and heightened morale.

There was more opportunity at the reformatory for education, training, recreation, and varied treatment programs, which address individual needs and created opportunities post-incarceration. Failures of the reformatory came from criticisms and opposition from politicians and prison guards who did not see eye to eye with the case workers trying to support the goals of the reformatory.

Punishment was continued as this was a past theory that continued into the reformatory that punishment would alleviate criminal behavior, and security above all won out. Though very minimal, escapes did happen, and security took precedent. And all in all, without all of these theories of the reformatory being supported, the whole system failed. Caseworkers were not properly trained, and guards were also not properly trained to support the ideals of the reformatory.

In 1922, we see Jeremy Bentham’s idea of the Panopticon from 1791 realized in the United States. This was based on the idea of control through surveillance, solitary confinement, and labor. Very similar to the early ideas we see from the penitentiary. But this came to the United States much later.

The Panopticon was Jeremy Bentham’s theory of observance. Meaning that, as long as you’re being watched or think you’re being watched, you will behave appropriately. This model was based on continuous solitary confinement, labor in the cell, and controlling behavior through constant surveillance.

As you see in the floor plan here, and the image to the left, there’s a guard in the tower, but those incarcerated don’t know if they’re being watched or not, but the possibility that they are, controls their behavior.

The Panopticon was first realized in the United States in 1922 at the Stateville Correctional Center in Stateville, Illinois. This was called the round house or the F house. The result of this design is poor acoustics, very loud echoes happen throughout this space. It is mentally and emotionally degrading because they are constantly feeling like they are being watched. And it was an antiquated design. Safety and operational hazards occurred and led to the shutdown of this facility. The F house remains built due to its historical significance. And it actually reopened in 2020 to create social distancing for COVID 19 for those incarcerated.

In the 1970s, we see a brief experiment in bringing high rise carceral facilities to the urban context through the MCCs or Metropolitan Correctional Centers. This was based on the idea of humane design in the urban context. But in reality, these prisons look very similar to any other facility outside of the city. The only difference is they build up rather than build out, but this is due to the constraints of urban development.

The Chicago MCC, which is actually a jail rather than a prison, it is more of a short-term facility, by architect Harry Weese, is a great example of this theory of bringing correctional centers into the urban context. Hidden in plain sight, many people walking down the street would not realize this is a prison. The Chicago MCC is a 28-story triangular footprint and the individual cells inside were modeled on boat cabins with built-in furniture and tall narrow windows.

The image at the center of this slide shows the circulation opportunities that those incarcerated might experience during their stay here. They will not hit the ground plane and their only connection to the outdoors is the rooftop exercise yard. The result of the Metropolitan Correctional Centers, they do reduce travel costs from distant prisons to the courthouse when those incarcerated need to travel. But they were designed to be hidden in plain sight, that sort of disguise, not allowing the public around them to know that they are there. This is a missed opportunity to engage those incarcerated with the surrounding community and the amenities that it has to offer in education, healthcare, and social interactions.

Over the past 200 years, we have witnessed several designs for prisons promising reform, but they have all resulted in simply detaining those incarcerated until the end of their sentence. Mostly due to overcrowding, the reform theories could not keep up with growing populations. In response to this growing population the individual prisons have been combined over the time, creating large complexes.

Seen here is the New Jersey State Prison, which is actually America’s oldest operational prison opened in 1798 and operating today. You can see how over time different additions have been added. You can see the Auburn rectangular plan, the Pennsylvania system of the radial plan, and a modern addition to the bottom of the complex. This all designed to house 1200 individuals.

We see the same trend happening across the country, from California to Michigan to Louisiana. Louisiana happens to be the largest corrections complex in the country where over 5,000 people reside here. Our need to over incarcerate has led to 2,292 federal and state prison facilities being built in the United States housing over 1.4-million people.

Looking at prisons over the past 200 years, the failures are in the one size fits all approach. What works for one person may not work for another and each period of reform focused on helping one type of person, excluding the reformatory period. The penitentiary has failed in the solitary confinement, silence, penitence, long sentences and large populations. Punishment has resulted in physical, mental and emotional degradation. Opposition between guards and caseworkers has deterred reformatory practices from being successful. And separating those incarcerated from their support systems on the outside leads to higher recidivism rates.

The successes, though minor, the lowered amount of violence from separating individuals into separate cells and meeting basic life needs, food and clothing being provided. But the big successes over the prisons of the past 200 years came in the reformatory ideals. Joint responsibility, individualized programs, small populations, positive spaces, opportunity, variety in program and design to fit more than just the one size fits all, heightened morale, and addressing the traumas of criminal behaviors.

Reform Now- it is 2020, and we are looking for new ideas of reform. So why don’t we learn from the past, take the successes and get rid of the failures. Revive and modernize the reformatory theories. Creating community style settings rather than isolating institutions will reflect the successful aspects of the reformatory, but we need to ensure proper training for staff and commit to the goal of addressing individual needs rather than strict security.

Ideas we can take from the reformatory are: joint responsibility, so everyone has a say; individualized programs to address each person’s needs; self-improvement; small populations; connections with society are critical; and also is variety. Aspects for the design will include simulating a community modeled on the world outside of prison to alleviate the need to integrate with society upon release. Continual support during and after incarceration and indeterminant sentencing, release being based on achievements. All this can be done with cooperation and respect between all parties involved.

One very difficult aspect we have to overcome is the separation we have created between carceral facilities and society. 53.2-percent of those incarcerated are 100 to 500 miles from home. Of those people, 25.9 will receive visits. According to the Minnesota Department of Corrections, the average recidivism rate after one year of release is 43.3-percent. We can see a reduction of 13- to 25-percent in this recidivism rate when visitation from friends and family occurs.

In one of the most extreme instances I have found through my research is the Saguaro Correctional Center. This private prison is located in Arizona, but it’s contracted for the state of Hawaii due to land constraints on the Islands. In an article by the Marshall Project, a family of three discusses the difficulty in staying connected to loved ones incarcerated here. According to the Marshall Project, 1,391 Hawaiians are incarcerated in Saguaro. To travel to Saguaro to visit a loved one is over 8-thousand miles round trip. And the cost is over 2,000-dollars. Often times this can only happen one year at the most.

As I previously mentioned, I’ve visited Scandinavia to experience their positive approach to incarceration. And I’m aware that we cannot simply pick up their model and drop it into the United States expecting the same results. But there are many aspects I believe would translate. The first being, maintaining a ‘sense of self’ while incarcerated. The first day that I was in Finland meeting with the criminal sanctions agency, I referred to those incarcerated as inmates. They stopped me, and said, ‘we do not call those incarcerated inmates, we call them clients, because we as a society have failed them and it is our job to improve them’.

Next, traveling on to Sweden, I posed the question the first day that I met with the criminal sanctions agency there, I said, do you refer to those incarcerated as clients or inmates or those incarcerated, what do you refer to them as? And they looked at me strangely and said, we call them by their name. They simply call them by their name.

The second aspect we could bring back to the United States is simulating a normal lifestyle, which is what we have talked about with the reformatory. In Scandinavia, the loss of freedom is the only punishment. The third aspect is meaningful experiences. Also something that is present in the reformatory model, positive environments and interactions between staff and clients occurred daily.

One aspect that I believe really would maintain familial bonds is a reprieve. In the open prisons in Scandinavia, they’re allowed time away, maybe a weekend, to spend time with family and friends and really get a chance for a mental and emotional escape of incarceration.

While I was at Halden Prison, I spoke to this man in the picture playing the guitar, Sam Tax, and I spoke with him at length in his recording studio about the situation of prisons in Scandinavia versus the United States. And he said to me, this quote, “you must take this to America, treat people with respect and they will not be mean. if you give respect, you will get respect.” And this picture is Sam Tax and his band, which is guards at Halden Prison playing in the restaurant at Halden Prison.

I’ll leave you with this image from Vanaja Vankila, a women’s prison in Finland, which is designed to simulate a community style living and has proven successful, and there are very low recidivism rates.”

Janet: That was terrific. I just, I love it so much. First of all, I just wanted to say that the Auburn congregate system, I mean that picture of the man in that jail cell, I mean, he could barely move his elbows. It gave me a little bit of a panic attack. I don’t remember seeing it, in our practice runs and, or I just didn’t want to see it. I, like I said, I had a real visceral reaction and I’ve been reading some of the comments. And, the reformatory part, really we were moving in the right direction, and then for some reason we got distracted and here we are now in 2020 and I really think that the whole Scandinavia piece is so important. And just a little side note for all you people, is that Jana and I might be going in 2022 to Scandinavia with some students. We’re going to use our well-deserved vacation breaks to, to look at prisons. And maybe a couple of the mental wards, but I think it’s really fascinating that they call people by their names or they call them clients. And that picture, you really have to look hard at that picture with the musician. I mean, it looks like that would be at like your Oh, like country club.

Jana: It’s a gourmet restaurant because they have a, they focus on classes and training that really apply once the clients are outside of prison, because you know, these skills they need to get a job afterwards.

Janet: Again, I saw your presentation before, I was, I was making the connection. I said, Holy smokes. I see a China cabinet. I see wallpaper. I see a chandelier. I’m like, okay, we are, we are way behind. Well, Oh, and also seeing the feed, I just want to quickly add before I introduce Dana, and then I want your feedback real quick, Is the thing that I, again, looking at your piece prior, was it struck me, was the people move going from Hawaii to Arizona. It’s a plane ride over an ocean. And I think in order to help to keep recidivism rates down, it’s, I don’t understand where the disconnect is, I feel like that’s sort of prison 101 or human being 101. I don’t, I don’t understand why that seems reasonable.

Jana: Well, it’s all money driven, really. There’s not enough space on the islands and they don’t want to use the space to build a corrections facility. And there’s plenty of space in the mainland. And there’s a private prison there that will happily take the money. It’s all money driven.

Janet: Yeah. So we have to look at that. Thank you so much, Jana. We’ll bring you in again later for some question-and-answer period.

Jana: Thank you.

Janet: Thank you. And next up we have, Dana McKinney and Dana is quite accomplished. We’re very excited to have her. She’s an architect and urban planner and advocate, which, I mean check all those boxes. She graduated from Princeton with an AB in architecture. She has her master’s in architecture and urban planning, from Harvard Graduate School of Design and what is also kind of fascinating about it, she’s founder of Black and Design Conference, and as well as Map the Gap in African American Design Nexus. So welcome Dana. Did I get that all right?

Dana: Thank you.

Janet: Okay, great. So thank you so much for being here. I’m going to allow you to do your thing. And I’m, I’m going to, I’m going to check out,

Dana: okay

Janet: So I’ll talk to you later.

Dana: Awesome, thank you.

Janet: Thanks, bye.

Presentation (Live): “Before I get started, I just kind of want to introduce how I kind of fit into this conversation. While I was in my masters at the GSD, I decided to study the carceral system as my focus for my thesis, my architecture thesis. Having been working a lot in advocacy, in Black Lives Matter, in the NAACP and in the city of Boston I really wanted to focus on something that was extraordinarily emotional, relevant to me and my own family’s legacy and history, as well as something that I think would challenge myself, but not just myself, but also the university to look at issues that are kind of more socially oriented. And so, this is my thesis from that time called ‘Societal Simulations, A Carceral Geography of Restoration’.

So I wanted to go to the city that inspired me to become an architect and urban planner in the first place, which is Newark, New Jersey. Newark sits about nine miles from Manhattan, just for context. And it’s a historically black and brown city also known as the brick city. So this is the home that my mother and her siblings and my grandparents grew up in. It’s in a very nice neighborhood with tree-lined streets. It’s near one of the city’s more major parks.

However, as a child, I would go back and forth from my house, growing up in Connecticut, to this home in New Jersey. And to get to this house, when you get off the highway, you have to go through a city that is otherwise heavily blighted. And seeing that sort of discrepancy between the environment that my grandparents were in, the one that I was in at home, and the ones that just immediately surrounded their little haven, it really inspired me to look into architecture and the interface of architecture and planning.

So why Newark? Newark to me is sort of the telltale story of industrialized cities, or post-industrialized cities rather. And so the city, like many others in the East coast, really became to diversify in the 1900s, when, there’s a huge influx of immigration from Europe. And so this is just a map showing the different sort of ethnic racial pockets that started to establish over the city in that time period.

At one point in the 1930s, 1940s, the city really started to become like a bustling hub and almost served as a twin city to New York, really supporting financial services, especially such as insurance. And it also had one of the largest ports in the country.

However, like most American cities Newark was, I guess you can say, influenced by red lining. And so, there were significant swats of the city that only white residents were able to acquire property on. And most black and brown residents were then relegated to sort of these outer corners of the city.

In 1967, similar to other major cities at the time, there was a series of race riots. The main one took place over three days and resulted in significant damage of the downtown center, which again was sort of this twin to Manhattan. And as you can see in the next slide, it really resulted insignificant white flight. And so what’s sad about Newark is that it used to have like a huge amount of diversity across like, ethnic groups near Europe. You had blacks and browns people, but after that point, there was a significance of white flight.

And with that came sort of the incarceration of this urban condition itself. This is an example of a public housing development in the city, not too far from downtown. If you go to this development, there’s one way in, and one way out. The entire development has other gates, though, all of which have been padlocked closed. So, you would imagine this could have numerous implications in terms of fire hazards and life safety, but instead, this is how they treat a lot of the low-income residents.

There has been a lot of significance of blight, such as fires and graffiti and homes like this are spread throughout the entire city’s landscape. And that’s what stood out to me was that it feels like the city had given up on itself. And had prepared its population to be incarcerated. There there’s very little separation between the two. An example of the brick and the CMUs, this barbed wire, the chain linked fence and the graffiti. Again, this is everywhere across the city’s landscape. Incidents of gunshots going through windows. And again, barbed, I mean, having the plywood backing, it’s just a depressed environment and it feels like the prisons that surround it.

So here’s one of those prisons that surrounds it, the Northern State Prison. So this is one of the larger facilities for the state of New Jersey holding about 25-hundred people right now. You go to the next slide; you can see that it actually stands right next to Newark International Airport. But also sits kind of opposite the highway or opposite the train tracks from the waste management facility. So if you were to go onsite, you would smell all the waste that’s being processed on that facility. And for people who aren’t allowed to leave on a regular basis, it’s a pretty oppressive environment.

The city of Newark also houses one of the county’s juvenile detention facilities. And I’m sure some of you are aware, but for those who are not, juvenile detention has been kind of increasingly getting smaller, which is a good thing, kind of a recognition of the sort of detriment that juvenile detention has on people.

And this facility is interesting because it sits very close to downtown and it’s opposite a charter school and relative to a lot of other sort of residential spaces. And so it’s, I think it’s kind of harrowing for the youth that live in the neighborhood because they’re constantly aware of this sort of prospect of being incarcerated in a facility like this.

So with this urban condition in mind, 1-in-4 residents in Newark, New Jersey have a lifetime likelihood of being incarcerated. If you just let that sit in for a second, that’s pretty heavy. And this, it’s all part of a bigger system. It’s all part of the American carceral system. And so for bigger perspective, everyone should know that there’s 7.3-million people who are in the carceral system. There are four parts of that system, one being prisons and jails, so that’s incarceration, and then community supervision, being probation and parole.

Over time, so this is sort of the, the landscape of the carceral system. Over time that, those numbers have exploded, especially as a result of sort of things like the sentencing reform act, the war on crime, the war on drugs, the three strikes policies. Sort of in the early Obama administration, and there was a lot of federal pressure to sort of start decarcerating, especially among youth. But with that decarceration, there’s a whole litany of issues of what do you do with those facilities?

As an example, in the State of Connecticut, there are about fifty kids who are currently incarcerated in their juvenile detention system. To keep just those fifty kids in at a time it’s about a million dollars a year. So with fewer kids in the system, it’s great, but the cost to keep them in there is exponentially greater.

And this is just a breakdown of state, federal, and local jails, as well as juveniles facilities and, other facilities such as immigration detention. A lot of people think it’s just violent crime, but there’s also a huge proportion of drug and property and public order offenses.

And just another lifetime likelihood. It is, you cannot talk about incarceration without linking it to race and ethnicity. And so, there’s a 1-in-3 lifetime likelihood of black men to go, to, to be incarcerated. And 1-in-18 for black women. We should note that for black women especially that is the population that is growing the fastest currently. And there are repercussions of this for family destabilization, especially because you’re ripping away a lot of times, mothers from their children, mothers from caretaking for their adult older parents. But this is also an issue, an imbalance for Latin X men and women.

As we said earlier in this talk, 76.6-percent of people recidivise within five years, that is absurd. Given the cost that we are spending to supposedly rehabilitate people, the system is not working and we should all acknowledge that what we have right now is broken and it’s functionally flawed.

So, I want it to look at what the alternative could be. And I knew for one, I didn’t want it to be a prison. I think that the prison system as a whole is flawed, as I just said. And I think that we need to think about more innovative approaches that allow people to be, to remain in their communities, to keep family stabilized and to also stabilize communities, such as Newark.

And I approached the project by thinking about it as a village for restoration and inoculation for recidivism. The next slide basically walks you through all the things of spatially, aesthetically, materiality of what is currently versus what I aspire to in the future. And just the main things to think about are warmth, brightness, ecology, freedom, advancement. These are all metrics of, for me, what success could be in this new system. I want to focus on Newark again, because it was the space that inspired me to be an architect. And I want to focus on Baxter Terrace, highlighted here in orange. This particular site is the site of the first public housing project in the city of Newark.

If you go to the next slide you’ll see, it was this awful brick development built in 1941, which was actually segregated by floor plan. So by floor plate rather, every other floor. So black, white, black, for example. And then the facility was eventually torn down in 2012 because it was overrun by issues of sex trafficking and drugs and gang violence. And has subsequently just stayed vacant in the city. It’s a pretty significant parcel and it’s relatively close to downtown, but it’s kind of has this, people don’t really want to touch it. No developer has really proposed any efforts on it since then.

And so, I wanted to create a model that was the village, but the village has three major components, one of rehabilitation, which is restorative justice for me, empowerment. So including places of employment, as well as activities, because everybody deserves to have fun in my opinion, and security through housing. A lot of times we see that in recidivism people are actually getting picked up and going back to a jail or prison because they’re unable to secure housing. And housing insecurity in general in major cities is a huge concern. And so I just think that it’s important to allow somebody to properly rehabilitate that they have to feel secure in their environment.

I’m going to walk you through some of the design that I had done for this project. So this is the ground floor plan, as you can see. I was really hoping to not create something that would feel like it stigmatized the residents of the facility. And for one, it was important to maintain a street wall, cause that’s how the rest of the city is. And once you enter the site and once you become a resident of this facility, that’s when this sort of, the rigidity of the community starts to break down and it starts to open up to landscape and the amenities.